Blind Spots in Tech's Vision for Our Cities

As AI and innovation reshape urban life, we must ask: are these solutions truly solving the right problems?

As AI continues to dominate discussions about the future of cities, one crucial element is often overlooked: the widening gap between the private sector developing "AI" tools and the public sector focused on addressing real-world human challenges.

Many people I know in tech are eager to build something—not necessarily to solve a specific problem, but simply to apply the skills they learned in college or bootcamps. They’re often encouraged to create something that they believe will resonate with real users. While this can be fine for a side project, too often, people are chasing the idea of “building something” as a pathway to profit, with solving real problems becoming a secondary goal.

These same people often talk about building a better future for their users, adopting an altruistic mission. While some may genuinely have the best intentions, many are primarily profit-driven, earning millions by tackling problems that are often inconsequential. Even those with earnest intentions frequently lack the depth of knowledge needed to address the issues they aim to solve. As a result, the solutions they create are often forced to fit problems they don’t fully understand, making it challenging to drive meaningful progress in ways that genuinely benefit society.

Then these tech leaders are elevated to positions of influence and seen as thought leaders, often because they built something that gained market success—not necessarily because it addressed a meaningful issue. I see it much like when celebrities or athletes speak out on issues unrelated to their expertise; the key difference is that tech leaders are often granted the freedom to make impactful decisions because they have the financial backing to support them.

Schools and programs are attempting to address this "founder-first" mentality by including social science requirements in their curricula. However, these courses are often treated as just another box to check, with few students truly engaging with the insights they offer. It’s often only years later—prompted by social pressures or a broader push for well-roundedness—that people start exploring philosophy, art, and literature and realize the importance of truly understanding the people they’re trying to help. While founders are encouraged to "talk to users," it often amounts to little more than gathering another data point rather than developing genuine empathy. This gap in understanding is especially concerning in today’s charged political climate, where the importance of bridging divides has never been more urgent.

I feel it's fair to say this because I've worked at these companies myself, often told to follow the money without truly engaging with those on the ground who are working to solve these issues. Even when experts are brought on as consultants or assigned dedicated roles, if there’s no clear path to profitability, those strategies and solutions are ultimately sidelined or cut altogether.

This is just one of many startup fallacies, echoing the idea of "If you build it, they will come." The belief is that discovering product-market fit follows finding a founder who’s ready to commit for the long haul, willing to dig in and work hard to identify the right problem and solution. But this approach feels strange to me—how can someone be the right person to solve a problem they’ve never experienced or don’t fully understand in the first place?

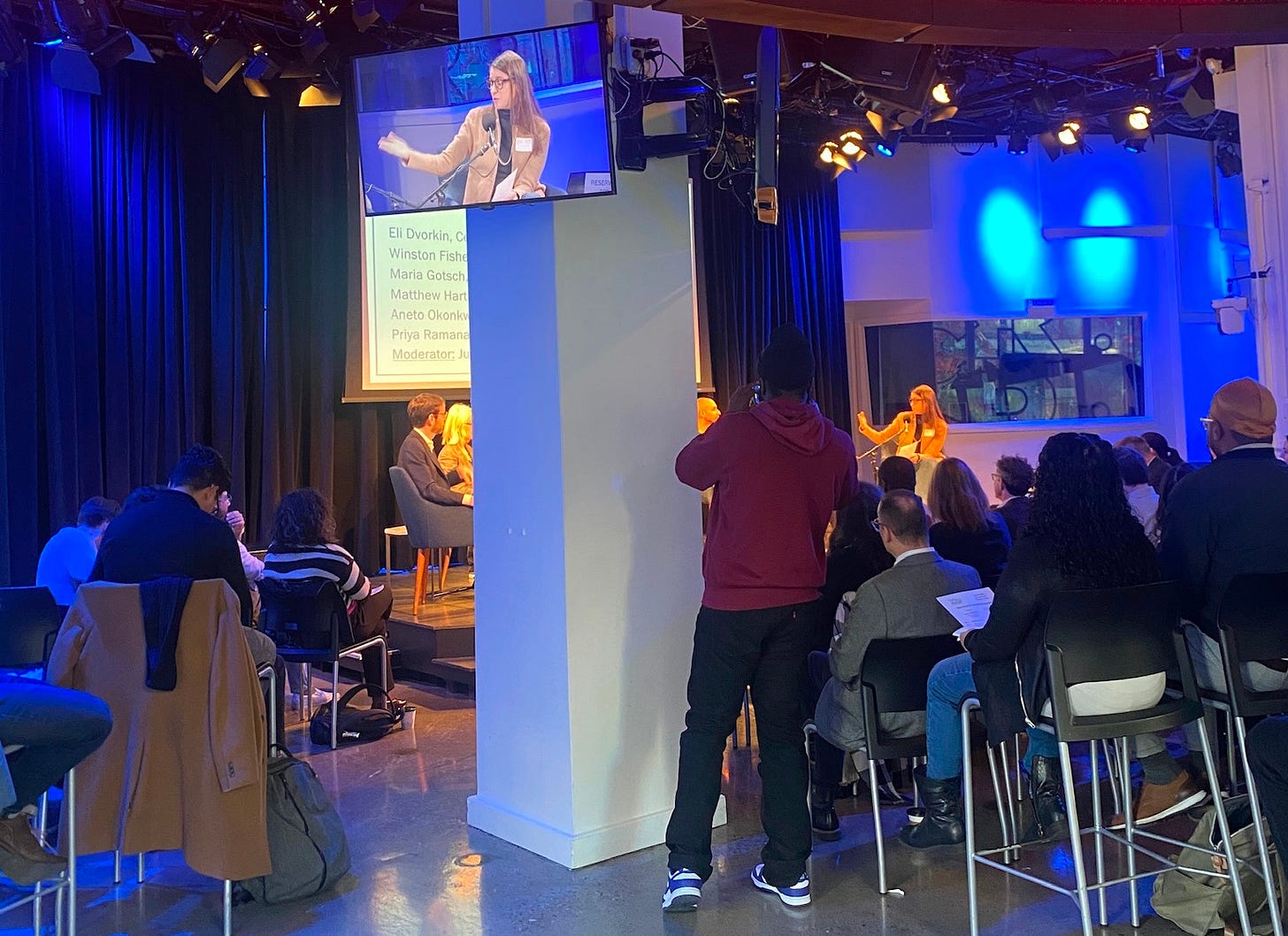

At events like today’s Center for an Urban Future’s discussion on Maximizing NYC’s AI Opportunity, panels are often assembled to explore how AI tools can be leveraged in the public sector. The panel I attended featured a distinguished group, including experts from think tanks, funding leaders, and startup CEOs. However, what was notably missing was someone from community organizing or those working directly on the ground—individuals who use AI in their everyday efforts to solve real-world problems for people.

One key area of discussion centered on how AI, much like the early days of the Internet, is currently an emerging industry that will eventually become ubiquitous, integrated across various sectors as a tool for innovation. There was also widespread recognition of the potential for AI to render some jobs obsolete, but the solutions offered for reskilling workers were vague. The focus was largely on teaching people how to use AI or pushing them into low-wage tasks like tagging AI training data, similar to Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, as a form of side income—without clear pathways to more sustainable future careers.

Another issue heavily discussed by startup and fund leaders, was the quality and formatting of data. I saw the problem stemming from leaders on both sides struggling with communication: first, by not clearly specifying the format the data should take, and more importantly, by failing to request the right data altogether. At the same time, most agencies responsible for ensuring the upkeep of data do not prioritize this work, nor do they see the immediate value of doing the work.

However, the biggest takeaway I had from the discussion was by Maria Gotsch, the CEO for Partnership Fund for NYC, who talked about why tech so often builds something without thinking of the consequences or working with the right people to make solve an actual problem.

For me, a prime example of this is the push for driverless cars. Proponents highlight numerous potential benefits, such as improved efficiency, safer driving, reduced traffic, lower costs, and increased accessibility. But do these advancements address the deeper issue—namely, why cars are harmful to society as a whole?

The core problem isn’t just how we drive; it’s car dependency itself. The ubiquity of cars creates a host of issues that impact our cities, our health, and the environment. For most people, car ownership and relying on cars for daily transportation shouldn’t be the norm. Our cities have been designed around cars, demanding extensive infrastructure like roads, highways, and parking lots. This layout consumes enormous amounts of space, fuels urban sprawl, and drives up costs for local economies.

Urban sprawl leads to more than financial strain. It requires vast amounts of raw materials like plastic, rubber, and metals for car production, as well as energy resources to power vehicles and maintain roadways. The spread-out nature of sprawl also results in high levels of emissions from heavy traffic, which contribute to respiratory health issues, a sedentary lifestyle, and noise pollution that disrupts mental health and local ecosystems.

Furthermore, this car-centric design leaves many neighborhoods as “transportation deserts,” with limited or no public transit options, which in turn increases social isolation and restricts mobility, especially for those who cannot drive or afford a vehicle. Urban sprawl forces people to spend more time in traffic when there are more efficient, sustainable ways to move people—like public transit.

The real answer isn’t simply making cars driverless. People can still have access to cars when needed through rentals or ride-sharing services, but private car ownership shouldn’t be the default. Until we rethink our dependency on cars, even autonomous vehicles can’t solve the fundamental issues tied to car-centric lifestyles.

This can be seen across the board with other “supposed” urban solutions like food delivery apps, e-scooters, online education, social media, and so much more.

Innovation from the private sector is essential, as governments will never be able to move as quickly. However, we shouldn’t fool ourselves into thinking that the private sector alone has all the right answers for solving societal problems. Government, community leaders, and researchers bring valuable insights into the everyday challenges people face. The leaders best suited to guide solutions are those with the deepest understanding of the field. This intersection of expertise and perspectives should be a priority when shaping the future, as these leaders not only understand the problems but also have the relationships and trust needed to address them effectively.

Winston Fisher, Partner at Fisher Brothers and CEO of AREA15, began the panel discussion by saying, "The future is here already," referencing a ride in a driverless car. But we must pause and ask ourselves— is this the future we truly want, or simply the one we think we should have?