Turning a Department Store Parking Lot into a Local Community Plaza

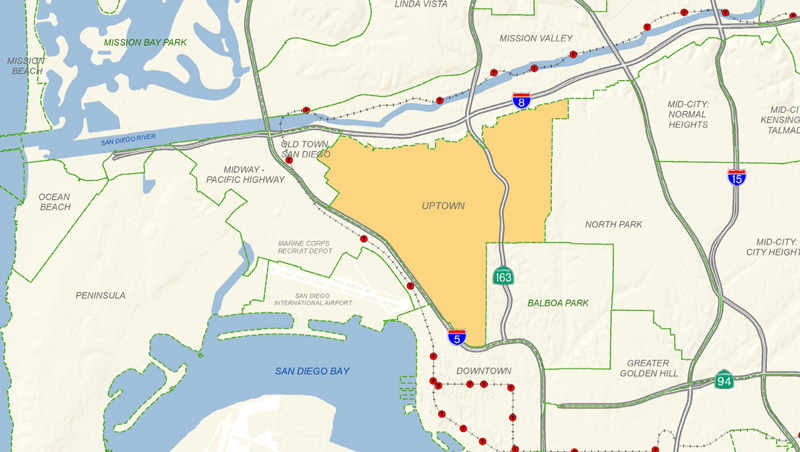

Let's take a closer look at a well known zoning case study: Uptown District, SD

While I’ve been looking into mixed-use housing and updates around improving zoning laws, one specific example often came up — Uptown District in San Diego, California.

This neighborhood is often cited as one of the earliest mixed-use approaches in a downtown area since the automobile became the dominant form of transportation back in the 1950s. A future article around mixed-use zoning and single-family homes will come, but I think setting the context with one obvious example can help level-set expectations for why changing zoning is so important.

I’ve personally had the chance to be able to walk through the neighborhood before when I drove to San Diego a few years back on my way to Balboa Park.

Repurposing the space

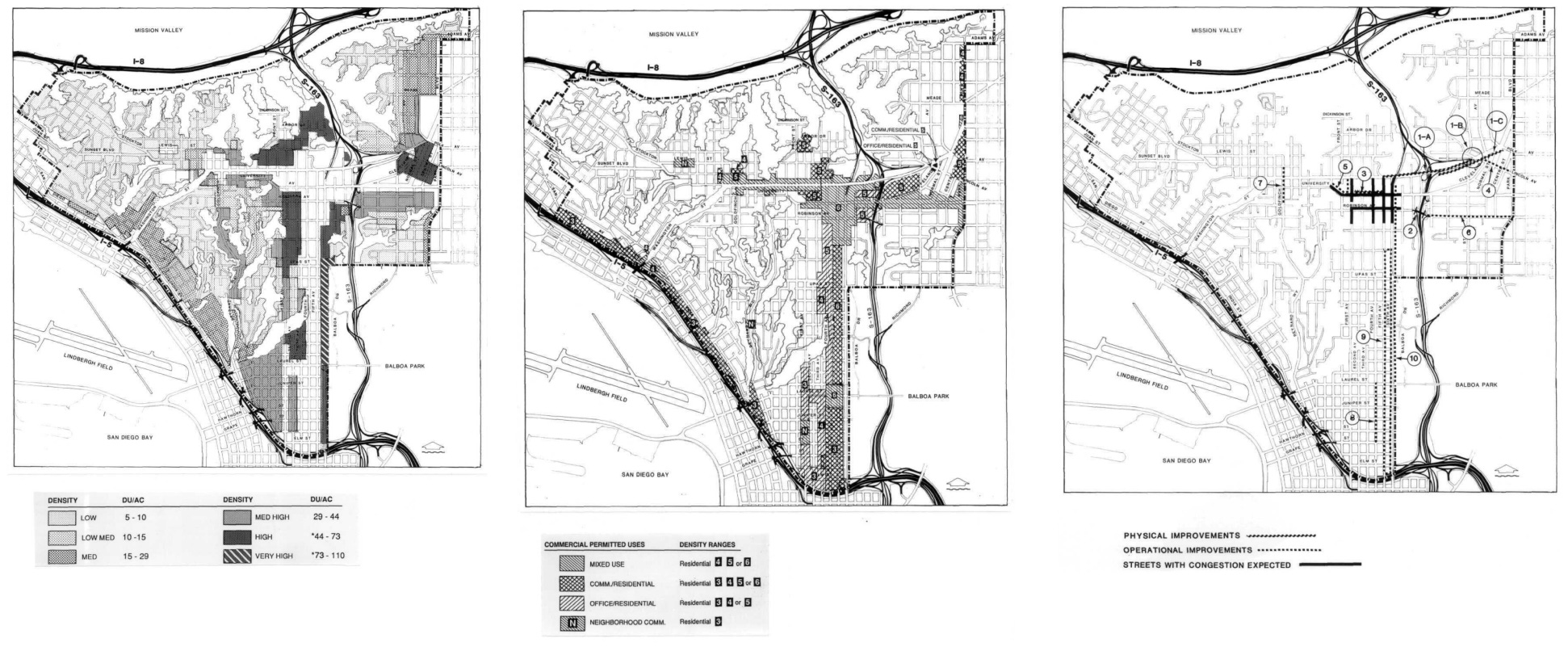

Before the re-zoning was a discussion in the Uptown area, there were a number of problems that started to arise. The original Uptown community plan was zoned in the 1930s, with multifamily zoning applied to a majority of portions in the community. Lower density zoning and single-family zoning was applied throughout.

Around 40% of these residential units that were still around in the 1980s were built during the 1930s-1940s. Around 36% of these homes were single family homes.

However, around 5% of these homes started to deteriorate, with many more about to deteriorate in the next decade or so. Much of the reason attributed to this deterioration is the location of the neighborhood near the airport. 18% of those deteriorating were multi-family units, and the population tended to be, on average, older with higher income and often fairly white.

“Homeowners had to put 50% down and pay it off in five years.”

- Ricardo Flores (SD LISC Executive Director)

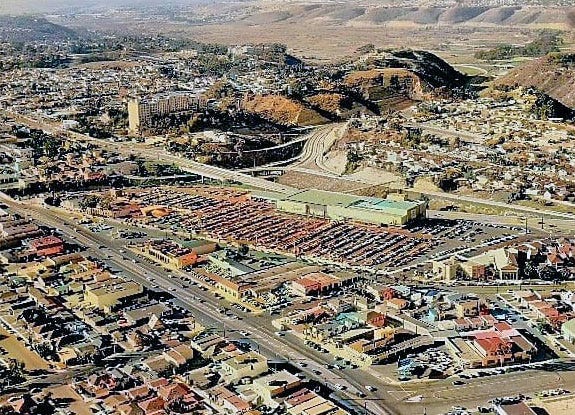

And so, as the community was trying to figure out how to create new housing and bring business to the area, they turned their eyes to a nearby giant parking space that sat alone — a 14-acre lot that Sears abandoned in 1984. The city of San Diego decided to purchased the space for ~$9M in Sept. 1986 to turn this ghostbox, or greyfield, into the new central library. A greyfield is a formerly-viable retail and commercial shopping space that has lacked in reinvestment and been "outclassed" by larger, better-designed, better-anchored shopping sites.

Working quickly, the local citizens instead persuaded the city council to allow for the Uptown Community Planners acquire and develop the site for something else instead.

Coming up with a plan

A series of community workshops were hosted by the Uptown Task Force with other community interest groups like the Hillcrest BA, the University Heights Community Association, and the Sears Site Review Committee. They landed on three main issues:

Not enough housing types and the loss of neighborhood commercial districts.

Minimal maintenance of public facilities and encroachment into public spaces.

Loss of clean, healthy spaces, and community character, history, and culture.

And they turned these problems into 5 main goals:

Provide a wide range of housing types for all age, income and social groups.

Revitalize neighborhood commercial districts, with a pedestrian-oriented approach that is safe and efficient for people and goods.

Establish a fully integrated system for vehicular, transit, bicycle, pedestrian facilities; while also preventing traffic through local surface streets.

Create public community and recreational facilities and services, including parks and centers; while also adding urban-oriented plazas, parkways, and streetscapes.

Preserve and enhance rich and varied cultural and heritage resources, and retain structures of historical value and character of the neighborhood.

Winning the bid

Working with the Oliver McMillan/Odmark and Thelan development team, the group put forth a plan to hit these goals, while still reflecting the surrounding neighborhood, winning the bid from the city and purchasing the lot for $10.5M.

The winning design came out to be typically “Mediterranean” with lots of elevation change, brightly colored awnings, manicured public spaces, public artwork, landscape parks, smaller blocks. It also connected surrounding neighborhoods with better streets and pedestrian pathways, including bridges and limited surrounding parking to encourage walking.

Surrounding areas also got rezoned, totaling to around 576 net acres complying with the new proposal and objectives, adjusting for mixed-use development instead as they worked to increase density and had new land use boundaries. Minimum required standards for landscaping, floor area ratio, building height limits, yard and setback, etc. were set up to fit the new regulation.

The residential area got 318 new homes, with over 20 units per acre of residential density and 3,000 square ft for community center space. This drastically outpaced the rest of the cities less than 3 units per acre, creating a much more dense neighborhood.

Commercial and retail saw the addition of around 145,000 square ft., with a commitment and interest to support local businesses. The plan continued active efforts with Business Improvement Districts (BIDS) to revitalize the space with ongoing events and public facilities. A six-year program was set up to provide public community engagement, while also rezoning facilities as appropriate.

City-owned parks and open space were also rezoned to the new Open Space Zone requirement, while also changing privately owned open space to better fit the new residential spaces. Throughout the entire area, fire-resistant trees and plants were added to beautify and preserve the space.

Ironically, parking spaces did still get added, matching around 2 per townhouse, 1.7 per apartment and 1 per 270 square feet of commercial floor space. This is slightly less than the rest of the city which hovered around 2.25 spaces per residential unit and 1 per 250 square feet of commercial area. However, what was unique at the time, was that much of this parking space was not just created off streets, but rather built underground.

In addition, a survey was established to identify and maintain historic and significant buildings, so new development would accurately match the cultural aesthetic.

All of this work spurred development and redevelopment in surrounding neighborhoods like Hillcrest and University Heights.

But it hasn’t all been fine and dandy

As time has gone on, some of the work hasn’t gone according to plan.

Other than the main Ralph’s grocery store, the retail, office use and restaurants have not done well. A number of places have tried to support themselves in the space, but quickly go out of business including a coffee shop, local clothing stores, a chicken rotisserie shop, an Italian restaurant, a travel agency, and even a yogurt shop.

"University Avenue [where much of the retail is located] desperately wants to return to more of a pedestrian orientation, but the dynamics there are still mainly auto-driven, and as a result the side streets will feel like a backwater ... The retail component has been the most problematic to pull off ... Success requires a lot of tinkering over a lot of years."

— Peter Katz, author of The New Urbanism: Toward an Architecture of Community

Personally, I can see why this neighborhood may not continue to be as thriving as many case studies may say the place should be. While the mixed-use zoning regulation helped give the space an opportunity to make changes, the execution of design still left much to be desired.

While walking around the neighborhood, I felt like much of the actual space looked the same. The cohesive design, while may have lent itself to one aesthetic, did not appear to lend itself to a great diverse inviting environment. Nothing really stood out between one building to the next, making it feel like each business was the same. If you’ve ever walked around any suburban plaza in California, I think you’ll especially know what I’m talking about.

There also did not appear to be any community engagement supposedly brought about by the local public facilities. Perhaps I came on the wrong day, but the entire place felt like it was a small local pullout plaza, mainly to find parking or go grocery shopping, rather than as a place to go out and get food with friends and family.

But there is continued hope for the space.

Recently, the Uptown District sold for $81.1M in 2016, exchanging hands after foreclosure from original developers during early 1990s. The increased development in 2016 to the surrounding Hillcrest, Bankers Hill, and Mission Hills area also suggests a reinvestment in the neighborhood. And the 2019 Community Plan appears to address local housing issues by increasing density, building a new streetcar service to downtown, relaxing parking requirements, and allowing for more flexibility with units including ADUSs.

Still, I feel like more needs to be done around the design to better incentivize people to walk around and shop in the community — or perhaps the “Mediterranean” design of the space just isn’t for me.

For more information about the Uptown District, feel free to check out my list of sources. If you’d like to read this in a presentation format, check it out here.

Oh and a small fun fact: The originally planned library on the lot finally opened in downtown in 2016, 30 years after it was originally announced for the Sears lot.